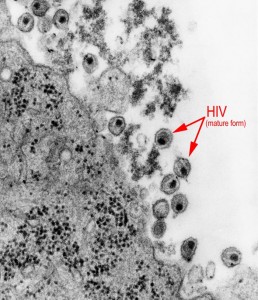

A new gene editing technology, termed the CRISPR/Cas9 system, has been used to remove any genetic remnants of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from cells in culture. The system removed all traces of the viral DNA, eliminating the virus’s ability to replicate within the cell.

There is currently no cure for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), the disease caused from HIV. In the past 15 years though, huge advancements in pharmaceutical drug manufacturing have turned AIDS from a death sentence to a chronic condition, extending patients’ lives by decades through the use of antiretroviral therapies. New targeted technologies are emerging, such as the CRISPR/Cas9 system, that allow specific cells and genetic elements to be tinkered with, eliminating the side effects from drug cocktails. While promising, these newer technologies have so far only further extended life for patients without hope for a cure.

The CRISPR system is present in all eukaryotic organisms, and confers resistance to foreign genetic elements (plasmids, viruses, etc.). It does this by recognizing the foreign element, then modifying its own gene to develop a protein (Cas) to specifically combat the foreign genes presently and in the future. The CRISPR/Cas9 system takes advantage of the complex’s ability to recognize specific DNA elements. Researchers can modify the CRISPR system to target a specific gene of interest, then use the Cas9 protein to cut the gene, much like a Cas protein would normally cut foreign DNA. This allows targeted removal of specific genes, for use in studying diseases where genes are modified or removed, or to test therapeutic approaches, like the removal of HIV from cells.

Researchers from Temple University showed that by using CRISPR/Cas9 targeted to the genomic ends of HIV, they were able to entirely remove the viral DNA from different chromosomes of different types of immune cell lines. While the technology has been proven before in removing HIV, this new study removes the virus from multiple cell types, even certain subsets of T cells where the virus can hide for decades before becoming active again. “We were extremely happy with the outcome,” said lead author Dr. Kamel Khalili. “It was a little bit…mind-boggling how this system really can identify a single copy of the virus in a chromosome, which is highly packed DNA, and exactly cleave that region.”

Daniel Stone, a staff scientist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, remarked, “It’s really convincing that the approach has promise. The next question is, how do you deliver this?” The CRISPR/Cas9 system cannot be given like a normal drug, because it will be degraded or excreted rapidly by the body.

Dr. Khalili is currently working on a nanoparticle drug approach to package the system and target it to the lymph nodes, where HIV infects immune cells. He is hopeful though, saying “We have to optimize the system, [but] I think we have enough in vitro cell culture data and expertise to justify moving on to the next step [of testing in animals].”