After recent reports of locally acquired Chagas disease in a dozen people in Texas, plus hundreds of dogs, the media has been flooded with hundreds of reports on the Triatomine bug, or kissing bug and the parasitic infection it can carry, Chagas disease.

Image/Rachel Curtis-Hamer Labs

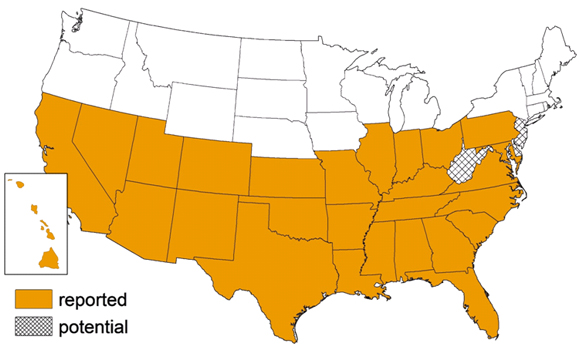

In July 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that 11 different triatomine species were found in at least 28 US states (see map below).

In an interview with the founding dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Dr. Peter Hotez two years ago, he suggested the number of cases of Chagas disease in the United States to be somewhere between 300,000 and 1 million. The United States is ranked 7th among nations for the amount of cases.

Most cases diagnosed with Chagas contracted it outside the country.

What is Chagas disease?

Chagas disease is transmitted naturally in North, Central, and South America. In parts of Mexico and Central and South America, where Chagas disease is considered highly endemic, it is estimated that approximately 8 million people are infected.

The Triatoma or “kissing” bug frequently carry for life the parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi. T. cruzi is a comma shaped flagellated parasite and the cause of an acute and chronic disease called Chagas.

In Chagas disease-endemic areas, the main way is through vector borne transmission.

Trypanosoma cruzi can also be transmitted via congenital transmission (mother to baby), through blood transfusions and organ transplants, and some cases of transmission through feces contaminated food.

The triatoma bug can be found in poorly constructed homes, with cracks and crevices in the walls or those with thatch roofs. They can also be found in palm trees and the fronds.

Usually at night while sleeping, the insect feeds on people or other mammals. While feeding the insect defecates and the infected feces gets rubbed into the bite wound, eyes abrasions or other skin wounds.

The parasite invades macrophages at or near the site of entry. Here they transform, multiply and rupture from the cells 4-5 days later and enter the blood stream and tissue spaces.

Initial infection with Chagas is typically asymptomatic. Acute disease may manifest symptoms after a couple of weeks.

Reddening of the skin (Chagoma) or edema around the eye (Romana’s sign) may be seen, albeit uncommon.

Fever, malaise, enlarged liver and spleen are part of the acute syndrome. 10% of people develop acute myocaditis with congestive heart failure. This acute disease can be fatal.

After a latent period which may last for years, the infected person may develop chronic disease (20-40%). The most serious consequences are cardiomyopathy (in certain areas it’s the leading cause of death in men less than 45 years of age) and megacolon/megaesophogus.

About 150 mammals beside humans may serve as reservoirs of the parasite. Dogs, cats, opossoms and rats are among the animals.

Diagnosis for Chaga’s is by finding the parasite in a blood sample or by antibody detection.

There is no vaccine for Chaga’s, so preventive measures should include insecticide spraying of infested houses.

Insecticide-impregnated bed nets may reduce the risk of infection for travelers who cannot avoid camping, sleeping outdoors, or sleeping in poorly constructed houses in endemic areas.

Nifurtimox or benznidazole is used to treat in the acute phase. These drugs are available in major hospitals in endemic areas.

Chagas can be a costly proposition, according to a recent study published in the The Lancet Infectious Diseases, where societal and healthcare costs for each infected person in the United States averages $91,531.

So, how worried should you be about contracting Chagas here in the US? Not very according to one expert. Sarah Hamer, assistant professor of epidemiology at Texas A&M’s veterinary and biomedical school said in an interview with CNN, “It’s great we are heightening our awareness — but we don’t need to be terribly scared.”

However, Baylor researcher, Dr. Kristy Murray says, “The high rate of infectious bugs, combined with the high rate of feeding on humans, should be a cause of concern and should prompt physicians to consider the possibility of Chagas disease in U.S. patients with heart rhythm abnormalities and no obvious underlying conditions.”

Related:

- Wellcome Trust grant goes to UGA and Anacor to develop Chagas drug

- Chagas parasite, T. cruzi, ‘widespread’ in Texas kissing bugs: Study

- Bedbugs can acquire and transmit the Chagas parasite: Penn researcher

- Venezuela: Chagas outbreak affects 12, oral transmission suspected

- Chagas drug, fexinidazole, goes into Phase II trials

3 thoughts on “Kissing bugs found in more than half the US: What is Chagas disease?”