New culture-independent tests are much more sensitive than traditional diagnostic methods in detecting the cause of infectious diarrhea, a significant problem that leads to nearly 500,000 hospitalizations and more than 5,000 deaths in the United States every year. But because these tests are so sensitive and may detect multiple organisms, infectious disease expertise may be necessary to interpret the clinical significance and facilitate appropriate public health surveillance, according to new infectious diarrhea guidelines released by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Designed to guide primary care physicians and other healthcare providers who see most children and adults with diarrhea, the guidelines note that the majority of people with diarrhea do not need to be tested.

Those who should be tested include children younger than five, the elderly, people who are immune-compromised and those with bloody diarrhea, severe abdominal pain or tenderness or signs of sepsis (life-threatening response to infection).

“Diagnostic testing combined with clinical expertise is helpful in identifying a cluster of infections that may signal an outbreak,” said Andi L. Shane, MD, MPH, MSc, lead author of the guidelines and associate professor of pediatric infectious diseases, Emory University School of Medicine and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. “However, even if they don’t need to be tested, most people will benefit from rehydration therapy while waiting for the infection to run its course.”

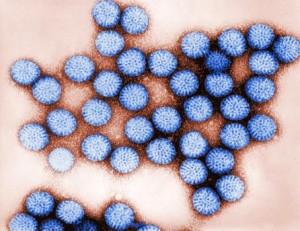

Diarrhea is defined by the World Health Organization as three or more loose or liquid stools in 24 hours, or more frequently than is normal for the person. Diarrhea is often – but not always – infectious, meaning that it is thought to be caused by a microbe such as a virus, bacterium or parasite that can spread from person to person. However, overall the most common causes of infectious diarrhea (also known as acute gastroenteritis) is are unknown. When new molecular tests are used, pathogenic E. coli and norovirus is are among the microbes most frequently identified in people with diarrhea. While infectious diarrhea is most common in children younger than 5 years of age, its incidence has decreased in the last decade since vaccines for rotavirus were introduced.

New culture-independent diagnostic tests developed in the last several years are more sensitive than the culture-based tests traditionally used. However, they may detect organisms with which most physicians are unfamiliar, or detect more than one microbe. In those cases, consultation with an infectious diseases physician may be beneficial, the guidelines note.

The guidelines include seven tables that busy clinicians can quickly reference for information about the various ways people acquire the microbes, exposure conditions, post-infectious symptoms and clinical presentation, as well as recommended antimicrobial, fluid and nutritional management. The tables also help clinicians assess when a person with diarrhea should be tested and provide treatment considerations. Physicians should ensure that children with mild to moderate dehydration, and children and adults with acute diarrhea and those with mild to moderate dehydration associated with vomiting or severe diarrhea be given oral rehydration solution if tolerated, progressing to intravenous rehydration if oral rehydration is not tolerated.

The guidelines also underscore the vital role primary care clinicians can play in identifying an outbreak.

“We need the frontline clinicians to be astute and notice if they are seeing patients with an unusual infection, or a number of similar infections from a specific location such as a child care center, nursing home or eating facility and then work closely with the state and local health authorities,” said Larry Pickering, MD, a co-author of the guidelines and adjunct professor of pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. “This is the optimal way to develop community awareness and use an integrated approach to identify and contain an outbreak.”

The new infectious diarrhea guidelines provide an update of the 2001 guidelines. While the guidelines mention travel-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile diarrhea, other more-specific guidelines on those topics provide detailed guidance and are referenced.

An related accompanying editorial in the same issue of Clinical Infectious Diseases notes that other organizations such as the American College of Gastroenterology have provided additional specific criteria for diagnostic testing for acute diarrhea, such as individuals with moderate-to-severe symptoms or illness lasting more than 7 days. “Culture-independent diagnostic tests are a game changer. A specific diagnosis can direct appropriate therapy and provide information regarding the likely course of illness,” writes Ferric C. Fang, MD and Robin Patel, MD, CID editors and authors of the commentary. “Moreover, a specific diagnosis can facilitate public health surveillance efforts.”

Related:

- Legionnaires’ disease cases reported in British travelers to Spanish town

- Plague news: Updated Madagascar case counts, Seychelles samples test negative

- Lymphatic filariasis in Nigeria: The battle against the disfiguring parasitic disease

- Yemen cholera outbreak closes in on 850,000 cases

- San Diego County reports 19th hepatitis A death as six out of 10 cases are reported in the city