In June 2018, an outbreak of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 (cVDPV1) was declared in Papua New Guinea following laboratory confirmation of cVDPV1 isolation in two healthy community contacts of the index case.

Image/CDC

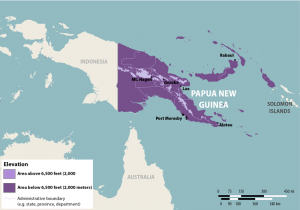

Since the declaration, a total of 26 confirmed cVDPV1 cases have been reported in nine provinces.

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies said recently that the epidemic is fairly under control. The declaration of Polio outbreak has yet not lifted.

The last laboratory-confirmed case reported experienced the onset of paralysis in late October 2018.

Since the outbreak was declared, there have been five rounds of Supplementary Immunization Activities (SIA) conducted from July to December 2018.

Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance continues to be enhanced and all provinces are now reporting cases of suspected AFP. As Papua New Guinea shares a border with Papua Province, Indonesia, cross-border surveillance and immunization has been discussed. A SIA has also been implemented in Papua Province, Indonesia in addition to the strengthening of surveillance efforts.

What is a vaccine-derived poliovirus?

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative says Vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPVs) are rare strains of poliovirus that have genetically mutated from the strain contained in the oral polio vaccine.

The oral polio vaccine contains a live, attenuated (weakened) vaccine-virus. When a child is vaccinated, the weakened vaccine-virus replicates in the intestine and enters into the bloodstream, triggering a protective immune response in the child. Like wild poliovirus, the child excretes the vaccine-virus for a period of six to eight weeks. Importantly, as it is excreted, some of the vaccine-virus may no longer be the same as the original vaccine-virus as it has genetically altered during replication. This is called a vaccine-derived poliovirus.

- Ireland: North Dublin reports measles outbreak

- Measles epidemic: 80,000 cases, nearly 1,000 deaths in Madagascar

- Measles in Ukraine: 9th fatality reported

- Nipah virus reported in Thakurgaon, Bangladesh

- Norway: Two reindeer killed due to suspicion of rabies

- Iceland reports 2nd measles case

- Finland officials warn of norovirus increases

- Sri Lanka reports 8,900 dengue cases in 1st two months of 2019

One thought on “Papua New Guinea polio: ‘The epidemic is fairly under control””