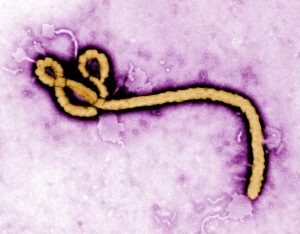

The World Health Organization (WHO) says the increasing number of new Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is deeply concerning. Fortunately to date, geographic spread is still limited to two provinces and there is no spread to neighboring countries.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Ministry of Health (MOH) has reported 1466 confirmed and probable EVD cases and 957 deaths, with 891 in confirmed cases since the outbreak began last year.

Over the weekend, 49 new confirmed cases and 43 deaths among confirmed cases were reported.

WHO reports Katwa is still the main focus of the outbreak, reporting nearly half of the cases in recent weeks. 484 confirmed cases and 329 deaths have been reported from the Katwa health zone.

This outbreak remains one of the most challenging ever in terms of the situation on the ground, calling for extraordinary response measures.

- Dengue outbreak in Dili, Timor-Leste

- Asia: Dengue cases up in the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia

- Measles in Ukraine: 100,000 cases and 35 deaths since summer of 2017

- Meningococcal meningitis update for Nigeria

The Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) continues to spread despite an extensive (and expensive) vaccination program. The overall case fatality rate remains high (>60%). In Ebola treatment centers, almost all patients have been given one or more investigational antiviral treatments, yet their case fatality rate is still >40%. Mistrust and community violence continue and healthcare workers have frequently come under attack. Political leaders in the DRC and internationally recognize the gravity of the situation, but except for a new ophthalmological screening program they have nothing new to offer. It needn’t be this way. During the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone in 2014, approximately 100 patients were treated with a combination of a generic statin and an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). Statin/ARB treatment targets the host response to infection (not the virus itself) by countering the loss of vascular barrier integrity which is a hallmark of the disease. WHO staff opposed this treatment, there was no support for a proper clinical trial, and the results were poorly documented. Nonetheless, treated patients showed “remarkable improvement” in survival. Local health officials refused to allow this information to be released to the public and WHO has never shown any interest in validating it. Now, five years later, as the Ebola outbreak continues, health officials in the DRC need to ask why this promising approach to patient treatment is still not being tested.

References

1. Enserink M. Infectious diseases. Debate erupts on ‘repurposed’ drugs for Ebola. Science 2014; 345:718-9.

2. Fedson DS, Jacobson JR, Rordam OM, Opal SM. Treating the host response to Ebola virus disease with generic statins and angiotensin receptor blockers. MBio 2015; 6:e00716-15.

3.. Fedson DS. Treating the host response to emerging virus diseases: lesson learned from sepsis, pneumonia, influenza and Ebola. Ann Transl Med 2016; 4:421.

4. Fedson DS. What treating Ebola means for pandemic influenza. J Public Health Pol 2018; 39:268-82.