In a follow-up on our initial report of leptospirosis in Puerto Rico post Hurricane Maria, the state epidemiologist for Puerto Rico, Dr. Carmen Deseda said at least 76 cases of suspected and confirmed leptospirosis, including a handful of deaths, have now been reported a month after Hurricane Maria struck and devastated the island.

Two deaths involved leptospirosis confirmed through laboratory testing, and “several other” deaths are pending test results, Deseda said.

The island typically sees between 63 and 95 cases per year, she said. Health officials had expected that there would be a jump after the hurricane.

“It’s neither an epidemic nor a confirmed outbreak,” Public Affairs Secretary Ramon Rosario Cortes said at a news conference Sunday. “But obviously, we are making all the announcements as though it were a health emergency.”

LISTEN: Puerto Rico crisis: What are the infectious disease risks post-Hurricane Maria

Analyst with the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Christopher Hurtado, MHS wrote in an article recently that there were certain challenges to surveillance of leptospirosis in Puerto Rico and that a number of factors suggest that leptospirosis cases may become more prevalent in Puerto Rico in the weeks to come:

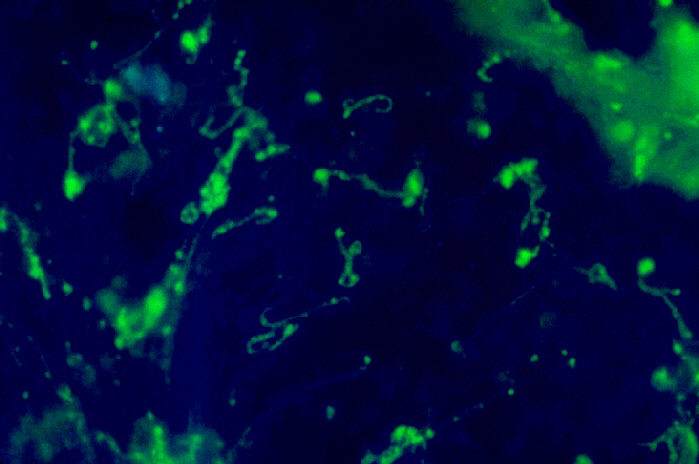

While the Puerto Rico Department of Health reported 729 leptospirosis cases from 1990-2014, these data likely underestimate the true burden of disease. Data from a previously released CDC MMWR report suggest that 60%-90% of fatal leptospirosis cases in Puerto Rico are not reported. There are at least three reasons for this. First, according to the CDC report, there is a “lack of timely diagnostic services,” with current methods generally considered time-consuming and requiring advanced laboratory services not typically available in remote or underdeveloped locations. Second, due to similar symptom presentation as dengue, many cases might be misdiagnosed. This is of particular concern in areas where dengue is endemic, such as in Puerto Rico. A third contributing factor to the underreporting of leptospirosis is the number of asymptomatic cases. A serologic study done on a 1995 outbreak of leptospirosis in Nicaragua found that only 29.4% of 85 seropositive patients reported febrile illness within two months prior to antibody collection.

A number of factors suggest that leptospirosis cases may become more prevalent in Puerto Rico in the weeks to come. While the scientific literature concerning post-hurricane infection with leptospirosis is scarce, one survey conducted during the 1996 leptospirosis outbreak in Puerto Rico found a “more than 4-fold increase” in laboratory-confirmed cases following Hurricane Hortense, from 4 out of 72 pre-hurricane patients, to 17 out of 70 post-hurricane patients. Additionally, out of the 17 confirmed cases of leptospirosis, 16 were male patients, who were believed to be at a greater risk for infection because of their assistance in “post-hurricane relief work.”

Floodwaters also provide ideal conditions for leptospires survival. According to the above survey, flooding “prevents [infected] animal urine from being absorbed into the soil or evaporating so leptospires may pass directly into the surface waters or persist in mud.” Puerto Rico residents may contract the bacterium either by drinking contaminated floodwater or swimming with open sores.

Related:

One thought on “Leptospirosis cases rise in Puerto Rico, May become more prevalent”