Between 10 and 16 March 2016, the National IHR Focal Point for Germany notified WHO/EURO of 2 cases of Lassa fever.

Details of the cases

- The first case was a medical health care worker evacuated to Cologne, Germany from Togo on 25 February for treatment of complicated falciparum malaria. The patient passed away on 26 February following multi-organ failure. Autopsy findings were suggestive of haemorrhagic fever, and Lassa fever diagnosis was confirmed on 9 March at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, Germany.

- The secondary case is a funeral home employee who handled the primary case’s corpse on 2 March. The patient is reported to have worn gloves and does not recall being exposed to bodily fluids. Following the primary case’s diagnosis, he had been under home quarantine since 9 March. He already had had symptoms of an upper respiratory infection when he had contact with the corpse. Symptoms waxed and waned over the following days. The first laboratory test for Lassa fever on 10 March was negative by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). When symptoms persisted, diagnostics were repeated and Lassa fever infection was confirmed by PCR on 15 March. The patient has been transported to a special isolation unit in Frankfurt. He has no history of travel in the 21 days prior to the illness. Four of his family members have voluntarily agreed to be quarantined in the same isolation unit. Further investigations are ongoing.

Public health response

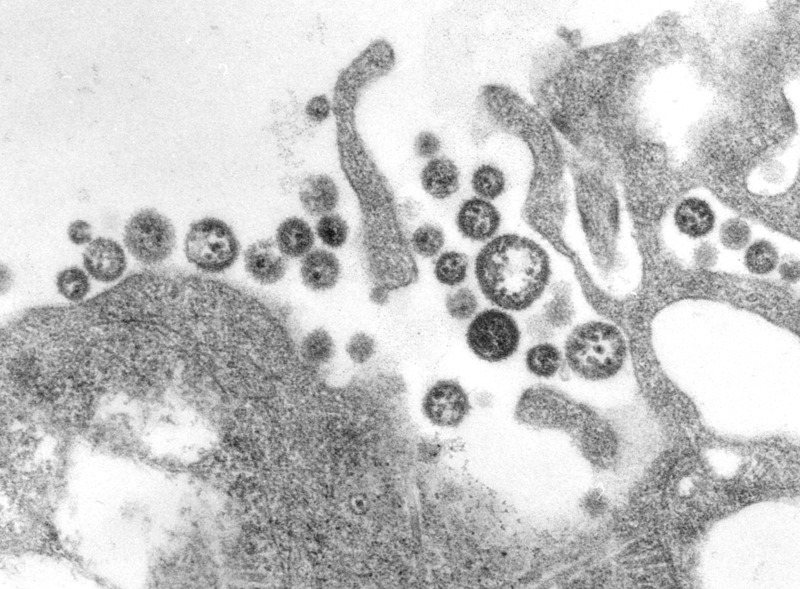

C. S. Goldsmith, P. Rollin, M. Bowen

Following laboratory confirmation of Lassa fever in the index case, 52 contacts have been identified and are currently under follow up. All contacts are either health care personnel or funeral home employees. For 38 of these contacts, the maximum incubation period (21 days) expired on 19 March. All contacts of the secondary case are also being followed up.

WHO risk assessment

Cases of Lassa fever have already been imported from West Africa to Europe. However, it is the first time that secondary transmission of the infection is reported in Europe. Risk for further transmission of Lassa fever in Germany is considered to be low and limited to hospital settings caring for the cases, with all contacts accounted for and monitored. WHO continues to monitor the epidemiological situation and conduct risk assessments based on the latest available information.

WHO advice

The secondary case identified in Germany underlines the need for all countries to ensure the application of standard infection prevention and control precautions when caring for patients, regardless of their presumed diagnosis. These include basic hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, use of personal protective equipment (to block splashes or other contact with infected materials), safe injection practices and safe burial practices.

2 thoughts on “WHO details Lassa fever cases in Germany”