The increased supply of safe water in a rural African community has significantly reduced the chances of children contracting a parasitic disease, according to new research in eLife.

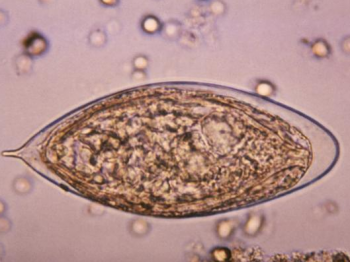

Image/CDC

The study, carried out in a community in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, demonstrated that increased provisions of safe water over a period of seven years have led to an eight-fold decrease in the risk of children becoming infected with urogenital schistosomiasis. This impact is substantially greater than previous results have suggested.

Schistosomiasis is a chronic parasitic disease caused by blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma. These parasites are transmitted by snails that live in freshwater environments contaminated by Schistosoma eggs. Urogenital schistosomiasis affects both men and women who can pick up the infection from agricultural, domestic and occupational activities that expose them to infected water.

“Recent work estimates that sub-Saharan Africa could lose $3.5bn of economic productivity every year as a result of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted worm infections, which is comparable to the 2014 Ebola and 2015 Zika epidemics,” says lead author Frank Tanser, Senior Faculty at the Africa Health Research Institute and Professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. “One of the main interventions to control schistosomiasis is the provision of safe water to limit contact with infected water bodies and break the cycle of transmission. But to date, a rigorous measure of the impact of safe water supplies on schistosomiasis is lacking.”

To understand this impact, Tanser and his team undertook comprehensive demographic and health surveys in a large rural population in KwaZulu-Natal over a seven-year period. An average of 10,267 households took part in each of these surveys, which asked participants to specify the most often used source of drinking water in their home. Households were deemed to have access to safe water if they reported their most common source to be piped water delivered directly to the home or from a public tap.

At the end of the survey period, the researchers then took urine samples from primary school children to determine the prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis, and found that 353 participants out of 2,105 – or 16.8% – had the infection.

The research took advantage of the large variations in the scale-up of piped water provision across space and time to capture the overall population-level impact of piped water on risk of infection. To accomplish this, the team used a novel approach that calculated the coverage of piped water in the unique local community surrounding each child in the cohort during the full study period. This community-level approach captured both the direct and indirect protection conferred by the scale-up. The results demonstrated that children living in communities with a high coverage of piped water were eight times less likely to be infected compared to those living in areas with little or no access to piped water.

“While there are some limitations to these findings, our approach provides a rigorous quantification of the overall impact of piped water on the risk of urogenital schistosomiasis infection,” Tanser explains. “The continued expansion of safe-water supplies and decreasing prevalence suggest that the disease is retreating and could even be vulnerable to eradication in similar settings, as long as strategies for controlling the infection are introduced and maintained.”

Related:

- Guinea worm disease: A discussion about the ‘fiery serpent’

- Dicrocoelium dendriticum: The lancet liver fluke

- Paragonimus: A look at this parasitic lung fluke

- Clonorchis sinensis: The Chinese liver fluke

- Parasites 101: Whipworm

- Parasites 101: Hookworms

- Pork tapeworm and cysticercosis

- Parasites 101: Entamoeba histolytica

- Diphyllobothrium: The largest known tapeworms that can infect people