Mumps: Background and Key Findings

A vaccine is a medical product that stimulates a person’s immune system to protect against a specific disease. The FDA assures the safety and effectiveness of vaccines for use in the United States, and only approves vaccines that it has determined to be safe and effective.

“Vaccines protect against serious diseases and save lives,” notes Steven A. Rubin, Ph.D., chief of the Laboratory of Method Development at the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

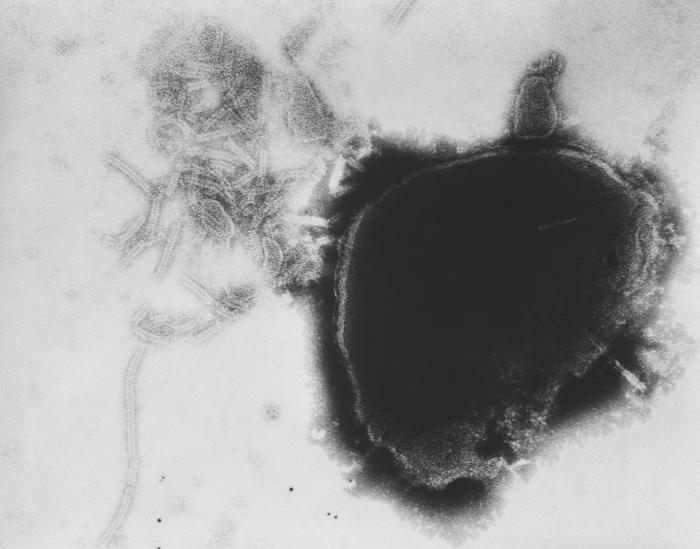

Rubin is studying immune responses to the vaccine used to prevent mumps, a contagious disease caused by a virus. Common symptoms include a swollen jaw and puffy cheeks—both due to painful swelling of the salivary glands—along with severe headache.

Although it rarely results in death, mumps can be serious. Before vaccines were developed, mumps was the leading cause of viral encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and sudden onset deafness in the United States.

Since the U.S. mumps vaccine program started in 1967, there has been a more than 99 percent decrease in the nation’s reported mumps cases. “Mumps is no longer common in the United States, but sporadic outbreaks still occur, even in highly vaccinated populations,” Rubin says. “Mumps was historically a disease of childhood, but outbreaks now typically involve young adults, particularly in high density, close contact environments such as on college and university campuses.”

LISTEN: Vaccines: An interview with Dr. Paul Offit

Today in the United States, children get two doses of a combination vaccine that contains a mumps component. “But our research indicates that by college age, levels of anti-mumps virus antibodies had declined substantially,” Rubin adds, which might leave people unprotected.

So, in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Rubin and his team studied college-age participants’ response to a third vaccine dose. Participants responded with a sharp increase in antibodies within the first month after vaccination, but levels went down to nearly pre-dose levels within one year.

“This suggests that an additional dose of vaccine is unlikely to provide a long-term solution,” Rubin says. “We are now looking into other ways of improving the vaccine, such as optimizing the structure of the vaccine virus to trigger the production of longer-lasting, more robust antibodies.”

Whooping Cough: Background and Key Findings

The FDA is studying whooping cough because rates have been rising steadily over the last 20 years. Also called pertussis, this serious and contagious disease is caused by a bacterium. It can cause violent and rapid coughing that continues until the air is gone from the lungs and a person inhales with a loud “whooping” sound.

“Pertussis is most severe and can be extremely dangerous in young infants, especially those who are too young to have completed the infant vaccination series against pertussis,” says researcher Tod J. Merkel, Ph.D., principal investigator at the FDA’s Laboratory of Respiratory and Special Pathogens. “Whooping cough can cause serious and sometimes life-threatening complications, permanent disability, and even death, especially in infants and young children.”

U.S. vaccines for this disease have a long history. The first “whole-cell” vaccines to protect against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis became available in the United States in the 1940s and contained killed, but “whole,”Bordetella pertussis bacteria. Concerns about side effects of these earlier vaccines led to the development of DTaP vaccines; the “a” stands for “acellular,” indicating that these vaccines contain only parts of the pertussis bacteria instead of killed whole cells. Acellular pertussis vaccines result in fewer side effects. The FDA first approved a DTaP vaccine in 1996 for use in infants as young as 6 weeks.

Today, Merkel is studying the pertussis vaccine in baboons, an animal model that closely reproduces the way whooping cough affects people.

LISTEN: Outbreak News Radio: Pertussis Vaccine Study

His findings suggest that although people immunized with acellular vaccines may be protected from whooping cough symptoms (sometimes referred to as being “asymptomatic”), they may still become infected. And these people can then infect others, including infants.

“That was an important finding. It provided a path forward,” Merkel explains. “Now our work is focused on trying to understand the ways we can improve the vaccine so it prevents infection and transmission, in addition to preventing disease symptoms.”

5 thoughts on “Vaccines: FDA researchers on the mumps and pertussis vaccines”