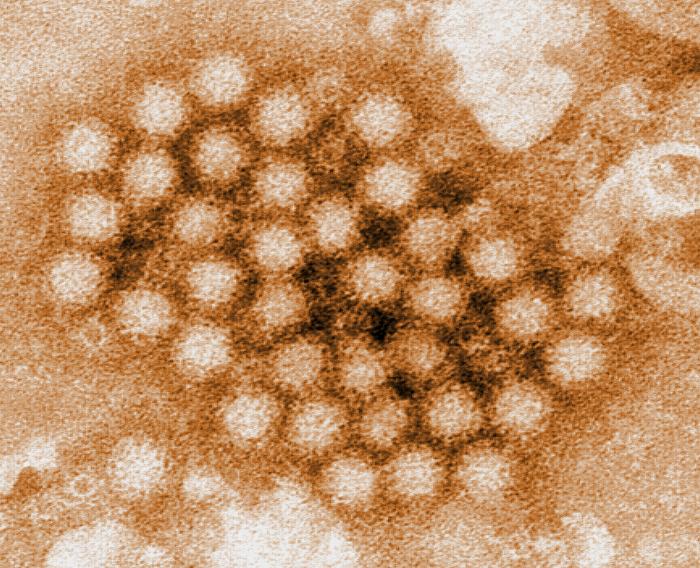

The news last week regarding a norovirus outbreak connected to a Chipotle restaurant in Boston comes in the wake of other foodborne illness outbreaks related to its restaurants which have infected over 50 individuals across nine states. This outbreak has sickened 140 college students, but it is unlike the other outbreaks related to an enterohemorrhagic E.coli strain; despite the obvious difference that the pathogen in this new outbreak is a virus, not a bacterium, it more likely presents the possibility of contamination from a sick worker at the restaurant.

The Bacterial Outbreaks

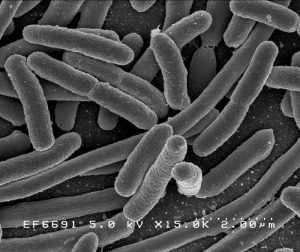

The cases involving the pathogenic strain of the bacterium, E. coli, appear allegedly to be related to meat or produce that was infected before it arrived at the various restaurants. It is not unreasonable to consider Chipotle a victim of the irresponsible practices of one or more of its suppliers of its food ingredients. In 2013, the CDC reported that between 1998 and 2008, fresh produce was responsible for 46% of all foodborne illness that led to hospitalization or death. Supervision of food manufacturers and suppliers is increasingly performed by less-than-objective third-party auditors in place of federal agencies.

However, the incidence of infection with the type of E. coli that causes bloody diarrhea and other serious complications seen in the Chipotle outbreaks appears to be actually declining (in the US, it had decreased in 2011 compared to 2006-2008 by 25%). Last week, while Chipotle’s CEO, Steve Ells, made a pledge that the chain will improve its food handling practices, a Chipotle restaurant in Seattle, which was one of 43 closed in Washington and Oregon in the initial outbreak, was closed again by health officials for failing to maintain foods at proper temperatures. Certainly, Chipotle has its work cut out for itself as it revises its traditional cooking procedures.

The Viral Outbreak

Norovirus, aka Norwalk virus, is the leading cause of foodborne illness in the United States, responsible for 42% of all foodborne outbreaks. Annually in the US, it sickens up to 21 million people, leads to approximately 71,000 hospitalizations and causes around 800 deaths. An infected person releases millions of Norovirus particles in their stool or vomitus, but only 10-100 viral particles (a minuscule amount) are required to infect someone else. Transmission occurs via the fecal-oral route: viral particles make their way to a person’s mouth on fingers that have made contact with an infected inanimate surface or via contaminated food. Because the virus resides within a relatively impervious protein coating, many disinfectants have no effect on it, including alcohol rubs; diluted chlorine bleach is the preferred choice and must be applied throughout a contaminated venue.

Sick Food Workers

The CDC estimates that 70% of norovirus outbreaks are caused by food contaminated by infected food workers. Overall, outbreaks of disease related to food consumption affect one out of six Americans, with 3,000 deaths each year; about 20% of foodborne illness cases are caused by ill food workers. The FDA mandates that food workers who are ill must notify their manager; in turn, managers must preclude workers with symptoms of diarrhea, jaundice or vomiting from all work areas. A recent study by the CDC found that although three-quarters of restaurants reviewed had sick worker policies, about a third were incomplete. The same study found that most managers left their workers to make their own decision to work, which 80% did while experiencing illness—10% worked while suffering nausea and other symptoms of gastrointestinal illness.

The US is the only one among 22 developed Western nations that does not require any paid sick days for its workers. American food workers, who often receive minimal wages, do not disclose their symptoms to avoid losing pay or to avoid encumbering their co-workers when replacements are not available at hand. A study in Philadelphia revealed that a third of its restaurant workers feared they would lose their jobs if they missed work. Connecticut and California, along with Seattle and New York City have passed laws requiring employers to provide sick leave. However, a recent survey of restaurant workers in Seattle discovered that 37% were unaware of the new law and 74% did not believe they had access to it.

The Costs of the Status Quo

It is not possible to determine if the outbreak of norovirus at the Chipotle restaurant in Boston originated from a customer or ill worker, although Chipotle reported that one of its workers had been sick the previous week. It is ironic that this scenario played out at within the Chipotle chain since it is one of the few nationally that provides paid sick time. Restaurants often operate on razor-thin margins, and prices for dining out in jurisdictions that stipulate sick leave will likely rise. However, restaurant lobby groups that are working to pass ‘preemption bills’ in state legislatures to block local sick leave laws may actually be doing their constituents and customers a disservice: the National Restaurant Association has estimated that a foodborne disease outbreak can expose a restaurant to an average of $75,000 in losses. The damage to a restaurant’s reputation and a chain’s brand can be devastating. The infamous outbreak in 1993, which involved Jack in the Box and sickened 750 children, required the chain’s insurer to pay out nearly $100 million. The cogency of denying restaurant workers the illness benefits that are available to workers in many other industries appears to be diminishing.

Steven Smith, M.Sc. is a Infectious diseases epidemiologist

One thought on “Denial of Sick Leave for Restaurant Workers in the US Comes at Too High a Cost”