A surge in Lassa fever cases in Nigeria in 2018 does not appear to be linked to a single virus strain or increased human-to-human transmission, according to a genomic analysis published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

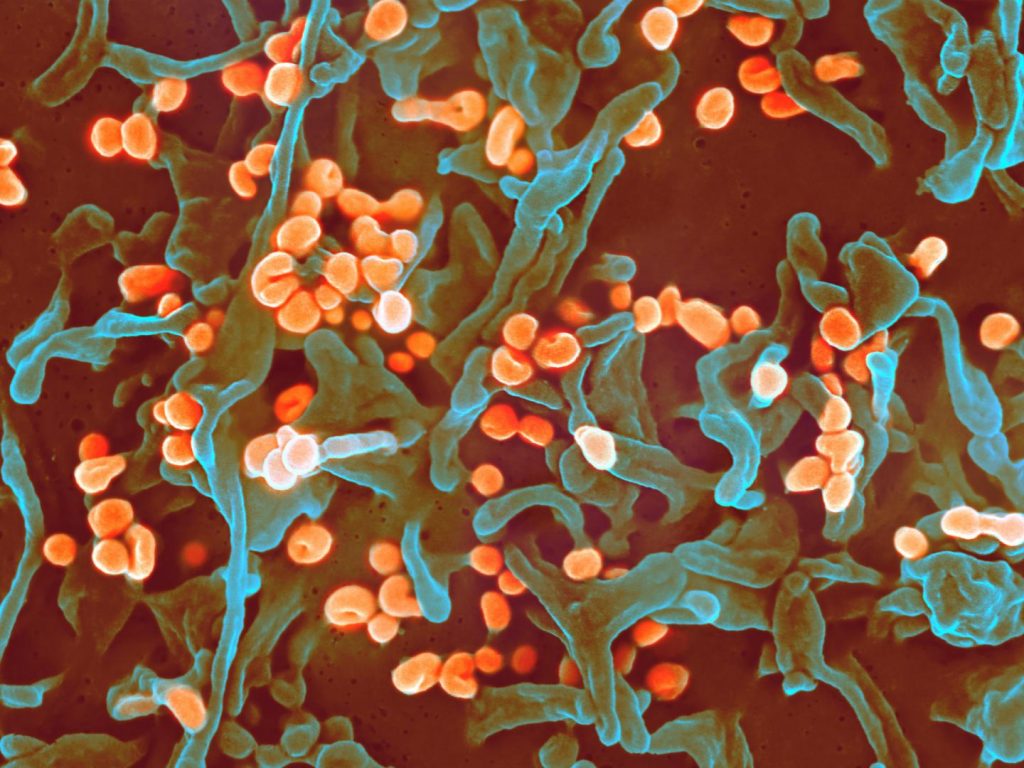

Image/NIAID

The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) reported an unusually large increase in Lassa fever cases in 2018, with 523 laboratory-confirmed cases and 135 deaths from January 1 through October 7. Lassa fever is endemic to West Africa, where Mastomys natalensis rodents, a primary animal reservoir of Lassa virus, are common. The rodent is often found in or around human habitats, and people become infected with Lassa virus through direct contact with rodent urine and stool. People with Lassa fever also can transmit the virus to other people through close contact, although experts believe this is rare. About 15 to 20 percent of people hospitalized with Lassa fever die from the disease, but only 1 percent of all Lassa virus infections result in death, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Public health officials were concerned that the Lassa fever outbreak in Nigeria in 2018 might be driven by a previously unknown factor, such as a new or more virulent Lassa virus strain, according to the authors. This prompted the research team to analyze Lassa virus genomes from patient samples to determine if genomic data signatures could explain the surge in cases.

The authors analyzed Lassa virus genomes of 129 patients from the 2017-2018 outbreak and from 91 patients from the 2015-2017 seasons. They discovered that Lassa genomes from 2018 were drawn from a diverse range of viruses previously observed in Nigeria rather than from a single dominant strain. This indicates that a single virus strain was not driving the surge in cases in 2018. Additionally, dating of the most recent ancestors of samples from 2018 showed limited support for human-to-human transmission. Rather, the dataset had features consistent with many, independent zoonotic transmissions (humans becoming infected through contact with rodent feces or urine).

The research team reported their findings in real time to the NCDC and local health authorities to support the public health response to the outbreak. The research serves as a model for investigating infectious disease emergencies by combining genomic information with traditional epidemiological data to inform response strategies, the authors note.

- How do malarial infections impact people exposed to Ebola virus?

- WHO: Current DR Congo Ebola outbreak not a international public health emergency

- Measles: More cases in Rockland County

- Hawaii mumps outbreak: Declared over after 1,000 cases

- Breastfeeding benefits: Protecting infants from antibiotic-resistant bacteria

- Chikungunya vaccine candidate progresses in Phase 1 study

- CDC on acute flaccid myelitis: ‘The number of cases reported in this time period in 2018 is similar to what was reported in the fall of 2014 and 2016’

- Gonorrhea cases jump 15 percent in Northern Ireland

- Battling biothreats: Dual anthrax-plague vaccine a strong candidate

- Dengue fever: Bangladesh reporting record year

- Zimbabwe cholera outbreak showing a downward trend, More than 9,000 cases reported